Troubleshoot Fire Alarm Ground Faults

🧰 What

and Where is a Ground Fault?

If it’s apparent that there truly is a ground, but it is not reporting, either the fire alarm system needs repair or *it has been tampered with by removing a ground jumper on the system.

*Note: On some fire alarm systems, there are jumpers that can be removed to disable ground faults. If this is found to be the case, call for technical help as soon as possible as this can impede the proper operation of the fire alarm system.

Example: If the ground happens to be on a smoke detector circuit, the system may not go into alarm upon activation of a detector. Disabling ground fault function is not only a potential danger to building inhabitants, but it is also against fire alarm codes to leave a system in this condition.

Why technician use the “disable ground” jumper on a

fire alarm system?

In most cases, the ground

disable jumper is used during troubleshooting procedures to silence the panel’s

annunciator while working on the system. The big problem is when a technician,

either purposely leaves the jumper on to “repair” the system or accidentally

leaves it on when finished troubleshooting.

There are times when the

technician has no control over their routing schedule or they forget to return

altogether. Besides, if one leaves the system in this condition, the building

(and its occupants) are left with a faulty system that can cause a false sense

of security. What if there happened to be a real fire and occupants die in a

fire?

If you are a technician,

find a ground fault, and for some reason can’t make the repairs at the time of

your visit, DO NOT disable this feature. Instead, put the appropriate sticker

on the fire alarm panel (describing the problem) and contact building

management authorities immediately.

You’ll sleep better at

night and you’ll also be heading off a potential lawsuit (even jail time, if

more serious).

🧰 Why Does a System Develop

a Ground Fault Condition?

🧰 Tools You’ll Need

Digital Multimeter

Ground Fault Locator (if available)

Insulation Tester (Megger)

Screwdriver / Cable Cutter / Flashlight

As-built Drawings & Zone Details

🧰 What are the causes of a ground fault?

Sometimes they are caused by

poor installation practices, such as attaching wires to all-thread hangers or

building structures above ceiling tiles. After being set in place for a period

of time, natural vibrations in a building can cause the wires to become worn

and eventually touch a ground potential.

Other times grounds can be

caused by other trades working in ceilings. If fire alarm wires are pulled or

accidentally brazed, this can expose the metal conductors of a circuit causing

an unwanted ground or short.

🧰 Use an Ohmmeter

Remember, if fire alarm circuit conductors are in contact with the grounded metal raceway or metal junction boxes, the problem will eventually be found using an ohmmeter. One or more circuit conductors will have continuity between it and a reliable grounding point. Finding the ground fault is only a matter of time and patience — and relatively easy to repair.

🧰 Multiple

Paths Used

To get a

signal from a device in the field to the control panel, or from the control

panel to a device in the field, the signal sometimes travels down more than one

path. Each path may be classified differently.

A pathway shall be designated as Class A when it performs as follows:

(1) It includes a redundant path.

(2) Operational capability continues past a single open, and the single

open fault results in the annunciation of a trouble

signal.

(3) Conditions that affect the intended operation of the path are

annunciated as a trouble signal.

(4) Operational capability on metallic conductors is maintained during

the application of a single ground fault.

(5) A single ground condition on metallic conductors results in the annunciation of a trouble signal.

A pathway shall be designated as Class B when it

performs as follows:

(1) It does not include a redundant path.

(2) Operational capability stops at a single open.

(3) Conditions that affect the intended operation

of the path are annunciated as a trouble signal.

(4) Operational capability on metallic conductors

is maintained during the application of a single ground fault.

(5) A single ground condition on metallic conductors results in the annunciation of a trouble signal.

If there's more than one control panel in the fire alarm system, these same signals could be sent over Class N pathways, which may involve fiber optics as well as CAT(X) wiring.

Regarding

any of the Classes of pathways (Class A, B, C, D, E, N, X), we as fire alarm

designers, installers, and technicians have to know whether a signal pathway

will allow a ground fault to affect the rest of the fire alarm system.

🧰 Coupled

Pathway

When

ground fault troubleshooting, a technician has to understand how various

communication paths work in a fire alarm system.

The pathway signals

can be divided into two groups: Direct Coupled and Indirect

Coupled.

Direct Coupled pathways would be:

·

The

Signaling Line Circuit (SLC)

·

Upload

& Download System Control and Power Loops (Four Wires - Plus, Minus, Send

to Devices, Receive from Devices)

·

RS485

circuit

·

RS232

Circuit

·

Power

Circuit (like for door holders, detectors, control circuits)

· Any other pathway that use copper wires, Like wet contact AHU Tripping, Damper operation control, Door Handling unit, solenoid activation ….. etc.

Indirect Coupled is not electrically

connected or hard wired - There is no electrical connection between any of the

electronic equipment or devices.

Indirect Coupled pathways would be:

·

Radio

Frequency (RF) Coupled like Wireless

·

Magnetically

Coupled (Transformer Coupled) like CAT(x)

·

Optically

Coupled like Fiber Optics

·

Any

other pathway that use copper wires, Like dry contact or through NO/NC AHU

Tripping, Damper operation control, PA Activation, Access Control Deactivation…..

etc.

🧰 Continuity

Test

🧰 Troubleshooting

Troubleshooting ground faults isn’t much different than troubleshooting any other electrical fault. Use a systematic approach to isolate the problem. In most cases there will be one or more conductors, or even whole circuits, that have made contact with a grounded piece of metal. Always keep in mind when it comes to fire alarm control units indicating a ground fault condition – sometimes a ground fault indication has absolutely nothing to with a grounded circuit. Every now and then there could be another reason — and that reason might be a little unusual – electrically speaking!

To find a

ground fault, the first thing you should do is *remove all wires from the fire

alarm control panel. If the ground trouble goes away, then you’ve ruled out the

possibility that it is not an internal ground within the control panel.

*Note: If you decide to remove one wire at a time instead of follow my advice (and there is actually more than one ground fault), then you may never see the ground trouble go away.

By removing all of the loop cables, you will rule out that the ground fault is not an internal panel ground. If the ground is internal, then you’ll need to replace the fire control panel or components within the panel.

If the

ground does go away, it’s time to break out the ohm meter.

To find a ground, click your meter to the highest continuity setting. Touch one of your meter leads to each conductor (not electrical circuits, of course) while also touching the other lead to a known ground. If installed properly, any electrical conduit is a good source to use as a ground reference.

Since you

are using a highly sensitive meter, make sure you are not touching or holding

any of the exposed wire leads with your fingers or you will skew the results.

Once you have found a ground, tag it and keep checking. Don’t assume this is the only ground fault.

After you’ve determined the source of the ground, it’s time to start troubleshooting in the field. If you have as-built drawings available (I know it’s rare), visually split the circuit in half and go from there.

Continue splitting the circuit into sections or areas until you narrow down the ground. If you find the ground is coming from the fire alarm cable between two devices, it is sometimes easier to simply replace the cable.

By bourn this issue need to counter and workout till it’s not gone.

If you are NOT an electrician or a licensed fire alarm technician, DO NOT attempt to make these repairs yourself. Only qualified personnel should make repairs and troubleshoot energized circuits.

If

you need further help in resolving fire alarm system issues, please contact a

certified commercial fire alarm company or electrical contractor in your area.

🚨 Common Causes of Ground Faults

Damaged

Cable Insulation – Cuts, pinches, or worn insulation causes direct contact with

grounded conduits or trays.

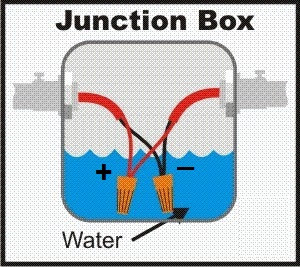

Moisture

Ingress – Water in junction boxes, devices, or conduits, especially in

basements, parking areas, or outdoor installations.

Improper

Terminations – Loose strands touching grounded backboxes or enclosures.

Screws

Piercing Wires – Device mounting screws penetrating cables inside backboxes.

Conduit or

Box Grounding – Conductors squeezed between metal parts.

Incorrect Use of Shielded Cables – Improper grounding of shields may create a path to ground.

🧰 Experience

Sharing

There are times when a ground fault indication on the control unit has nothing to do with a grounded circuit. The following is happening with SSA Integrate Engineer.

A fire alarm system with an

intermittent ground fault condition had been giving us fits for two weeks. This

was an older conventional system and did not indicate where the ground fault

was. In the middle of trying to figure out which circuit had the problem the

ground fault indication would go away. This made troubleshooting the problem

even more difficult. We inspected and tested each field circuit looking for any

indication of a ground fault and found nothing. We inspected inside the

junction boxes for bad or damaged conductors. We looked for moisture in the

conduit. We still found nothing. Then we even tried to narrow it down to a

certain time of the day, but there was no consistent time of the day for the

problem.

After two weeks, I happened to remove one of the batteries to clean the enclosure. I noticed there was a wet spot and paint had peeled up leaving a small area of bare metal. I checked the bottom of the battery. The battery had a tiny crack and was leaking a small amount of electrolytic fluid. The fluid would contact the bare metal. There was a complete circuit from the battery charger – through the battery – to the leaky fluid – to the grounded enclosure, which created a ground fault condition. We cleaned it up, replaced both batteries and did not have another issue from that fire alarm system. Luckily, we did not replace the control unit circuit board, as that would have not solved the problem. It was by chance that the problem was resolved.

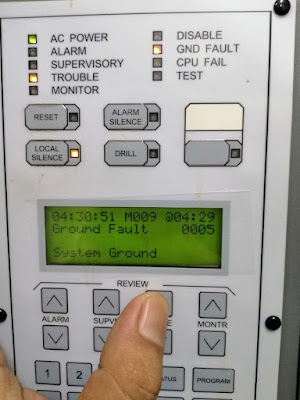

Another case we want to share,

customer reported Ground Fault trouble showing in there FACP. Standalone FACP

with 3 Loop System no Graphic software no BMS connectivity. Our Engineer visit

and find out once loop 2 cable are opened Ground fault is removed. Now team

just splitting the circuit into sections or areas until we narrow down the

ground. And ultimately found the ground is coming from the fire alarm cable

between two devices, simply we replace the cable.

Another case our engineer found Rubbing

the insulation on a sharp edge. It happened during installation of cooper

cable. Initial time it not effected in loop line. It is the cause of a lowered

insulation/voltage threshold. Even though the insulation is still covering the

copper, it is thinner at that point and the voltage required to push electrons

through the insulation is lowered.

On GST brand fire alarm control panel, on board one jumper is there to disable Ground Fault. Just open jumper to not showing Ground fault in Panel Display.

On Edwards or Notifier or Simplex, all are UL & FM listed panel. They don’t have such option to avoid ground fault.

🛠️ Step-by-Step Ground Fault Troubleshooting Process

🔧

Step 1: Identify the Type of Ground Fault

Check if it’s:

·

Positive (NAC/24V+) Ground Fault

·

Negative (COM/Ground) Ground Fault

Most panels can indicate which side is faulted. Check panel

diagnostics or use a multimeter if needed.

🔧

Step 2: Isolate Field Wiring (Loop)

Disconnect outgoing circuits one at a time (SLC, NAC,

IDC, etc.) from the panel.

·

After each disconnection, observe if

the ground fault clears.

·

If it clears, the fault is in that

circuit.

·

If not, continue isolating other

circuits.

🔧

Step 3: Divide and Conquer

Once the faulty loop is identified:

1. Go

to the midpoint of the circuit and disconnect. E.g. if you have

100 devices, split it into 50/50.

2. Check

both sides: Keep continue this process until you reach to the point and fix

this fault.

🔧

Step 4: Physical Inspection

·

Check all device boxes for moisture,

corrosion, or loose strands.

·

Inspect conduits for damage,

especially where mechanical works recently occurred.

·

Use a megger or ground fault locator

for more advanced detection.

✅ Pro Tips

Always label wires during isolation to avoid confusion.

Document findings – especially if you're working in a large

or multi-team project.

If working in a damp area (e.g., basements), ensure junction

boxes are IP-rated and sealed properly.

Don’t ignore intermittent ground faults—they often show up

only in wet or humid conditions.

🛡️ Prevention is

Better than Cure

Use proper cable supports and avoid over-tightening.

Train installation teams on neat termination practices.

Keep wires away from sharp edges or screw points.

Seal all junctions and outdoor boxes from water entry.

Regular preventive maintenance to check insulation and

terminations.